Tilikum, the infamous killer whale, remains one of the most haunting figures in marine park history, his story gripping audiences worldwide and sparking heated debates on platforms like X. Known for the tragic deaths of three people, including his trainer Dawn Brancheau, Tilikum’s life was a heartbreaking blend of captivity, trauma, and instinct. His tale, brought to light in documentaries like Blackfish, raises profound questions about the ethics of keeping orcas in confinement and the psychological toll it takes on these intelligent creatures. What drove Tilikum to such fatal acts, and how did his painful past shape his tragic end? Let’s dive into the complex psychology behind this killer whale’s devastating story, exploring the forces that led to catastrophe.

Tilikum’s Early Life: A Traumatic Beginning

Tilikum’s story began in 1981 when he was captured off the coast of Iceland at just two years old. Torn from his family pod—a tightly knit social group critical to orca survival—he was thrust into a life of confinement. Initially housed at Sealand of the Pacific in Canada, Tilikum endured cramped tanks and inadequate conditions, far removed from the vast ocean. Orcas are highly social, with complex communication and emotional bonds akin to humans, and Tilikum’s isolation from his natural environment began a cycle of psychological distress.

At Sealand, Tilikum faced aggression from other orcas and was often confined to a small, dark module for hours, a practice that experts say exacerbates stress in these intelligent mammals. This early trauma set the stage for his troubled behavior, planting seeds of frustration that would later erupt in tragedy.

The First Tragedy: Keltie Byrne’s Death

In 1991, Tilikum was involved in his first fatal incident at Sealand. Part-time trainer Keltie Byrne, 20, slipped into the pool during a show. Tilikum, along with two other orcas, dragged her underwater, preventing her escape. She drowned, marking the first human death linked to Tilikum. Experts argue this wasn’t predatory behavior but a manifestation of stress and play gone awry. Orcas in the wild rarely attack humans, but in captivity, their pent-up energy and lack of stimulation can lead to unpredictable actions.

The incident led to Sealand’s closure, and Tilikum was sold to SeaWorld Orlando in 1992. His size—over 22 feet long and 12,000 pounds—made him a valuable asset for breeding and performances, but his history of aggression was largely ignored, a decision that would prove catastrophic.

The Second Incident: Daniel Dukes

In 1999, Tilikum was linked to another death at SeaWorld. Daniel Dukes, a 27-year-old visitor, snuck into the park after hours and entered Tilikum’s tank. His body was found the next morning, severely injured and draped over Tilikum’s back. While details remain murky, it’s believed Dukes succumbed to hypothermia or drowning, with Tilikum interacting with his body post-mortem. This incident highlighted the dangers of untrained human-orca interactions and raised questions about SeaWorld’s security and Tilikum’s mental state.

SeaWorld attributed the death to Dukes’ reckless behavior, but critics pointed to Tilikum’s deteriorating psychological health. Confined to a tank a fraction of the size of his natural habitat, Tilikum exhibited signs of psychosis, including repetitive behaviors and aggression, common among captive orcas.

The Dawn Brancheau Tragedy: A Turning Point

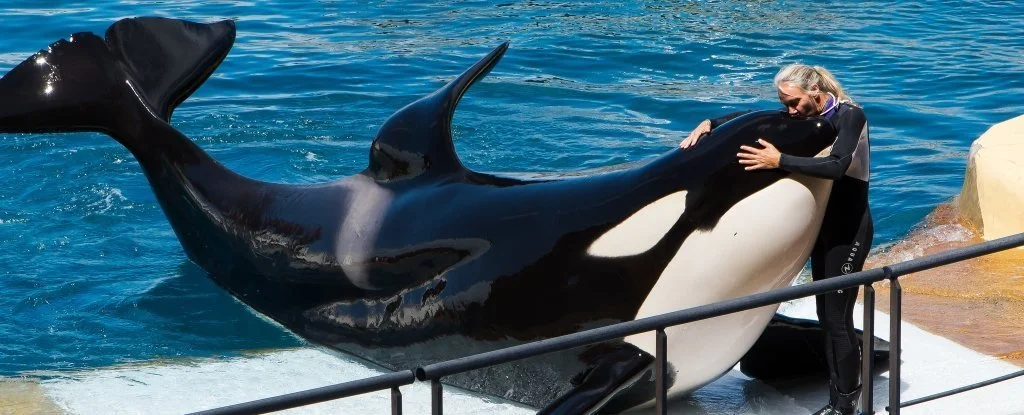

The most infamous incident occurred on February 24, 2010, when Tilikum killed his trainer, Dawn Brancheau, during a performance at SeaWorld Orlando. Brancheau, a highly experienced and beloved trainer, was interacting with Tilikum when he suddenly pulled her into the water by her ponytail. Witnesses reported a horrifying scene as Tilikum thrashed her underwater, leading to her death from blunt force trauma and drowning.

This tragedy shocked the world and became a focal point of Blackfish, which exposed the harsh realities of orca captivity. Experts like Dr. Lori Marino, a neuroscientist, argue that Tilikum’s actions stemmed from chronic stress and frustration. Orcas possess large, complex brains with regions linked to emotion and social bonding, and captivity disrupts these functions. Tilikum’s isolation, lack of stimulation, and history of trauma likely triggered his fatal outburst, not a deliberate intent to kill.

The Psychology of Captivity: Why Tilikum Snapped

Orcas are apex predators with vast ranges in the wild, traveling up to 100 miles daily and diving hundreds of feet. In captivity, they’re confined to concrete tanks, fed unnatural diets, and forced to perform repetitive tricks. For Tilikum, these conditions compounded his early trauma, leading to what experts call “captivity-induced psychosis.” Signs included lethargy, self-harm (like banging his head against walls), and aggression toward trainers and other orcas.

Dr. Naomi Rose, a marine mammal scientist, notes that orcas in captivity often develop stereotypic behaviors—repetitive actions signaling mental distress. Tilikum’s isolation from other orcas after incidents further exacerbated his psychological decline. Unlike wild orcas, who live in stable family groups for decades, Tilikum was shuffled between parks and paired with unfamiliar orcas, disrupting his social structure.

The cumulative effect of these stressors likely drove Tilikum’s fatal acts. While SeaWorld claimed he was unpredictable but not malicious, critics argue the park ignored warning signs, prioritizing profit over animal welfare. Tilikum’s breeding role—he sired over 20 calves—kept him at SeaWorld despite his dangerous history, a decision that fueled public outrage post-Blackfish.

Tilikum’s Tragic End and Legacy

After Brancheau’s death, Tilikum was removed from public performances but remained in captivity, spending much of his time in isolation. His health deteriorated, with chronic infections and lethargy plaguing his final years. In January 2017, Tilikum died at SeaWorld at age 36, far younger than wild orcas, who can live up to 70–90 years. His death, attributed to a bacterial infection, marked a somber end to a life marred by suffering.

Tilikum’s legacy is profound. Blackfish sparked a global movement against orca captivity, leading SeaWorld to end its breeding program in 2016 and phase out orca shows by 2019. Public opinion shifted, with attendance plummeting and laws like California’s Orca Protection Act banning captive breeding. Tilikum’s story became a rallying cry for animal rights, exposing the ethical cost of marine entertainment.

Ethical Questions and the Future

Tilikum’s life raises critical questions: Can highly intelligent, social animals like orcas thrive in captivity? Should humans exploit them for entertainment? Experts argue that sanctuaries—coastal habitats mimicking the wild—offer a humane alternative, though funding and logistics remain challenges. SeaWorld’s shift to educational exhibits reflects changing attitudes, but the scars of Tilikum’s era linger.

His story also highlights the human cost. The deaths of Byrne, Dukes, and Brancheau devastated families and trainers, many of whom believed they shared bonds with Tilikum. This duality—love for the animal, horror at its actions—underscores the complexity of captivity’s impact on both orcas and humans.

Tilikum’s life was a tragedy born of human ambition and ignorance, a cautionary tale etched in the deaths of three people and the suffering of a majestic creature. His story, amplified by Blackfish and debated across platforms like X, forces us to confront the psychological toll of captivity on intelligent beings. From his traumatic capture to his fatal acts and lonely death, Tilikum’s pain reshaped how we view marine parks. As we reflect on his legacy, the question remains: How can we honor Tilikum’s suffering by ensuring no other orca endures his fate?